18 months away from an approved coronavirus disease (Covid-19) vaccine, and even longer from having one available at scale. Despite vaccine development being at this uncertain early stage, India must immediately start planning how to deliver a Covid-19 vaccine.

When a vaccine becomes available, every onwill have to run the fastest and largest mass vaccination campaign in history. India will have to vaccinate about a billion people to reach the level believed to confer herd immunity for Covid-19. Each day of the virus-driven uncertainty cripples the economy and imposes immense human costs. India should do everything we can to save a few critical days, weeks or months.

A task force on coronavirus vaccine development, drug discovery, diagnosis, and testing exists. This group’s focus is diffuse. Even in the area of vaccines, the group’s focus is primarily vaccine development, not the delivery. Immunising a billion people in a country as diverse as India will be a staggering operational challenge. To be successful, we need a powerful group to plan for vaccine delivery now.

To pull this off, India can draw lessons from two large, successful campaign-style exercises. Every five years, India holds the world’s largest general election, involving up to 900 million voters. Electoral rules state there must be a polling place within two kilometres of every habitation. India employs 11 million election workers to make sure every eligible Indian can vote. Every vote is cast electronically via more than 1.7 million machines. Despite these formidable challenges, India successfully conducts elections, widely considered free and fair.

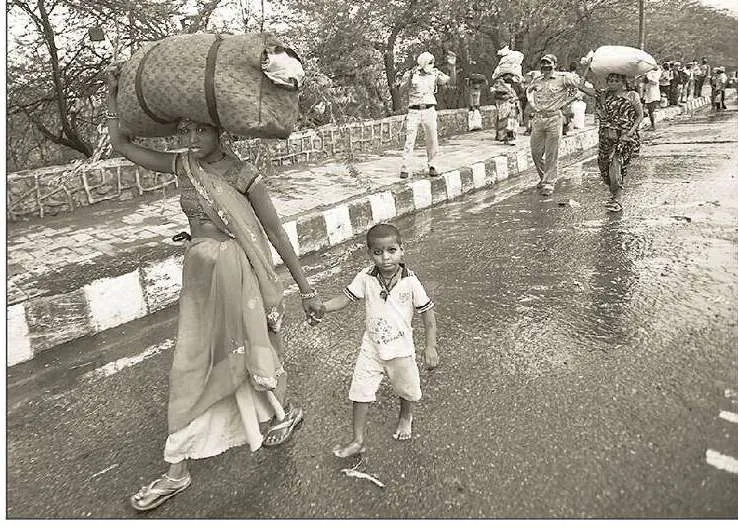

The polio campaign is the second example. As recently as 2009, India had over 60% of all global polio cases. With an annual birth cohort of 27 million children, high population density, poor sanitation, inaccessible regions, high population mobility and a high disease burden, the obstacles to achieving zero-polio status seemed insurmountable. Nevertheless, India has not had a single case of the wild poliovirus since 2011, and it was officially declared polio-free in 2014. The victory was achieved through government ownership, partnerships with private and social sectors, innovations in programme delivery, technical advances, and massive social mobilisation.

There are over 90 vaccine candidates in trials, six in human clinical trials, with more being added every week. The vaccine candidates range across virus, viral vector, nucleic acid, and protein-based approaches — which means that they will require different technologies and processes to manufacture them. We don’t yet know if an eventual vaccine will require temperature control, ultra-cold temperature control, or not require any cooling to maintain its potency. We don’t know if it will be packaged and administered via conventional syringes or an innovative new delivery mechanism such as a micro-needle patch. We don’t know the duration for which an eventual vaccine will confer immunity. We don’t know its efficacy; of the people who get vaccinated, what fraction will be protected from getting sick? We don’t know how that efficacy will vary across different populations — will it be as effective for older people as for younger people, for populations in north India as in south India?

Despite these uncertainties, there is a lot for a Vaccination Task Force (VTF) to productively focus its efforts on right now.

First, for each of the key uncertainty drivers, VTF can determine plausible ranges and identify the most likely options. These can be used to draw up a set of scenarios for detailed planning. The VTF can then monitor how vaccine development is progressing. As more information becomes available, the ranges on the key uncertain variables can be narrowed and the priority order and details of plans can be revised.

Second, practise through “war games” will allow decision-makers to rapidly and correctly react to changing circumstances. An example: How to react to the possible tragedy of a small cluster of deaths in one state, most likely due to vaccine-related side-effects? Such “war games” are standard practice for militaries, and are increasingly used by corporates to allow decision-makers to improve their responses.

Third, no matter how fast production can be ramped up, there will be initial periods when only a limited supply of vaccine will be available, and demand will exceed supply. The VTF can draw up allocation and prioritisation rules. For example, first high-risk populations such as health workers; then, vulnerable populations such as the elderly; thereafter, individuals likely to be potential “super-spreaders”; and finally, the general public.

The VTF can also represent India in global agreements for an equitable allocation of vaccines and agree to rules for the timing and allocations of supply within India versus for export to other countries.

Fourth, India excels in one critical dimension — vaccine manufacturing. India alone supplies 60% of the vaccine doses purchased by the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) each year. The Serum Institute of India is the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer, producing and selling over 1.5 billion doses annually.

Even if Indian manufacturers are part of global agreements to ensure equitable access to Covid-19 vaccines for every country, India can be assured of a strong negotiating position, as it brings critical production capacity to the table.

The VTF can work collaboratively with local manufacturers to understand how many doses can be manufactured in what time-frames, provide the necessary support to increase the number, and establish agreements to purchase a minimum number of doses at an agreed price.

Last, coherent, clear, and resonant communication will be a critical pillar for building trust and ensuring public receptivity and cooperation for a vaccination campaign.

If planning for vaccine delivery starts now, India will have a well-thought-through playbook to execute from when a vaccine is ready.