There is no nuanced way to say this. India is in the grip of a humanitarian crisis. And continuing the coronavirus disease (Covid-19)-sparked national lockdown will be an unmitigated disaster.

I have moved from being a reluctant votary of the initial lockdown — my understanding at the time was that it was a short-term inevitability — to an absolute opponent. I say this with the understanding that I have gained from a 60-day (and counting) road trip, reporting through nine different states in the north, west and south of the country. There is panic, paranoia, economic devastation and, above all, acute uncertainty on the ground.

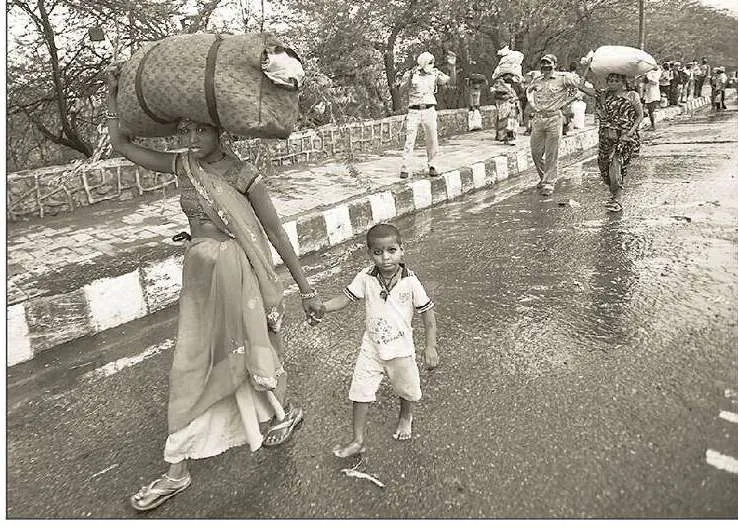

We have hit a psychological tipping point. This has become apparent to me every time I have walked the highways with migrant workers. In the initial 72 hours after the first lockdown, the mass exodus of workers from cities was because they had been forgotten by policymakers, politicians and the media. Orphaned by the system and left without wages or work, labourer after labourer, in state after state, told me that if confronted with death, they would rather die at home, with the people they loved.

But even after we went through a zillion flip flops on migrant workers — first they were ignored, then they were blamed, then they were asked to stay put, then they were asked to take trains for which they were charged fares — India’s workforce is in the throes of rage and anxiety.

It’s ironic that as some lockdown restrictions finally ease, and we are talking of reopening factories, the workers I meet are more determined than ever before to leave. In some ways, it is the comeuppance that some of the country’s businesses deserve.

But, even now, there is an assumption that, with the passage of time, these workers will return. My sense is different. In Bhiwandi, Maharashtra, it was past 1 am, when our car screeched to a halt at the sound of a child crying in the distance. In the deathly still of the night, we saw men, women and dozens of small children walking their way to Gorakhpur in Uttar Pradesh. They were going to cover a distance of 1,500 kilometres on foot. I ventured to suggest that they might try the trains and buses that have finally been deployed. They’d have none of it. They were just desperate to get home at any cost.

In Mumbai, a truck had been stopped at a police checkpoint. It was unclear whether the police was going to give it permission to move ahead and they did not appear keen for us to open the back flap of the vehicle. So, we clambered on to the back to discover scores of migrant workers crammed into a tiny space. They were looking to escape to Uttar Pradesh. One of them shouted at me when I tried to say crowding together might be dangerous at such a time. “I am a BSc. I am also aware of the coronavirus dangers. But I would rather die from the virus at home, than from starvation here,” he said.

These responses are a sliver of what I have been able to document from worker after worker over two months. I have met the family of Ranveer Singh who died 80 kilometres short of home from a heart attack in Agra, Uttar Pradesh. Or the family of Mukesh Mandal who sold his phone for ~2,500 to buy a fan and some rations, and then killed himself.

India’s poorest are suffering the most. But entire swathes of the salaried middle class are also in danger of being wiped out. Sectors such as aviation and hospitality are in existential trouble. Neighbourhoods are treating patients and health workers as untouchables. And society presidents are becoming bigoted tinpot dictators against domestic help, drivers and cooks.

We could have still suffered all of this had it brought us any closer to a cohesive policy against Covid-19. The lockdown’s aim was to prepare hospitals better, not eliminate the virus. But as I learnt in Mumbai’s Sion Hospital, where doctors speak searingly about why bodies are placed next to patients in wards, India’s public hospitals are still carrying a disproportionate burden.

Luckily for us, India has been an outlier in fatalities. In a country where thousands die from tuberculosis, cancer and kidney disease every day, the coronavirus death rates are not just distinctly lower than the rest of the world, but also way lower than deaths from non-coronavirus disease illnesses.

But if we do not lift the lockdown with immediate effect, we shall be confronted with mass ruin and a breakdown of all our structures — social, economic and emotional